|

|

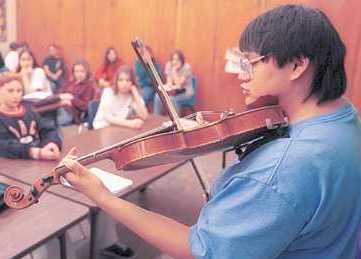

| Melissa Clark, 22, a

victim of fetal alcohol syndrome, plays the violin for students in a

life skills class at Paris Gibson Middle School. Clark visits

schools talking about her symptoms and trying to keep future parents

from making the same mistake her mother did.

-- Tribune photo by Larry Beckner |

|

Fetal alcohol syndrome leaves

its mark

March 15, 1999 Woman struggles daily

By Eric Newhouse

Melissa Clark, a 22-year-old victim of fetal alcohol syndrome, recently learned a painful lesson about trust. She was home alone in Great Falls when a man rang the doorbell. Although she didn't know him, she let him in. He walked to her bedroom, started to undress, and told her to do the same. She did. When it was all over, she called her foster mother, Johnelle Howanach, who called the police. But officers wrote it off as consensual sex. Not so, insisted Howanach. Clark's brain was damaged as a result of her birth mother drinking during her pregnancy, and she didn't know that having sex with a stranger is wrong. "People with fetal alcohol syndrome just don't have those boundaries," said Marilyn Kind, a friend who works with the developmentally disabled. "They are easily victimized," agreed Bill Hayne, a professor of education at Lewis and Clark College in Lewiston, Idaho. "They are eager to please, very friendly, and it leads to non-boundaries," said Hayne, who was raised on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. "They don't know the difference between a friend and a stranger because they can't remember." Learning boundaries is one of Clark's current tasks. "I have learned to say no to a lot of things," agreed Clark, "but I need someone to tell me when someone is not safe. "I don't want to go out with anyone unless my mom is there because guys can take advantage of you big time real quick." Clark wants desperately to be independent, but she knows that's not likely. "I jump in to do something, but I don't know what I'm doing," she said, "and it always turns out to be a disaster." One of the first children in Montana to be diagnosed with FAS, Clark combines an impulsive nature with impaired judgment. She gets tremendously frustrated when she can't do what she wants, when she can't do what others seem to do so easily. "I'm tired of people telling me what to do or putting words in my mouth," she exploded at Howanach during a recent interview. "I have my own opinions, and people aren't going to change my mind by putting words in my mouth," she snapped. But under Howanach's questioning, Clark admitted she lies at times. "A lot of these kids are tired of being 12, 15, 20 steps behind anyone else and they'll lie to make themselves look better," explained Hayne. Clark also admitted she has stolen money. "If there's not a definite physical connection to somebody, they think it's OK to take it," said Hayne "It's not stealing. It's like me taking a newspaper off a chair in an airport — it isn't mine, but I assume it was left behind so it's OK to take it." And Clark worries about what will happen to her when Howanach is no longer around to guide and protect her. For all her problems and worries, Clark is an amazing success story. When she was born Nov. 5, 1976, she was two months premature and weighed less than 3 pounds, 2 ounces. She remained in the hospital for 39 days. On Feb. 3, 1977, Clark's doctor noted: "This patient was a markedly premature child, Mother was an alcoholic, drank a lot. This may have something to do with the child's condition at the present." At a year and a half, Clark was diagnosed with what was then called fetal maternal syndrome. Social workers placed the child with Howanach in 1982, but said it wasn't likely she would be able to absorb an education. "She had an attention span of no more than a minute," said Howanach. "She was a truly hyperactive person — she was just swinging from the chandeliers." But after years of hard work, Clark graduated from C.M. Russell High School and reads at about a sixth- grade level, according to her foster mom. "That was hard," said Clark. "My reaction time was different. I was in a special education class, but it seemed that all the kids were two or three steps ahead of me. "They always seemed to have the answers when I didn't." Some of Clark's progress was because her foster mom worked with her, using simpler teaching tools. FAS children do better with art, music and tactile sensations than with concepts like English and math. Howanach emphasizes structure, going over each step of a simple process: how to cook spaghetti, answer a phone, do laundry. Stress is particularly hard for Clark to handle, as she found out when she got a job as a dishwasher. "I couldn't keep up with my job, and I broke two or three dishes," she said. "I was hanging in there for a while, but I kept getting behinder and behinder and finally I just crash bombed." Clark has made contact with her birth mother in telephone conversations that were painful to both. "It was a lot more than I could handle," said Clark. "When she started to talk to me about her drinking, I went over the edge and had to give myself space to deal with my emotions. "And she was crying so hard I couldn't really understand her." Now Clark has started her own business — she walks dogs for a small fee. And she uses the money to further what she has become her life mission: to educate the public about fetal alcohol syndrome. Her message? "Having fetal alcohol syndrome makes you feel like an animal all penned up in a big cage with a chain around its neck," said Clark. "But when the cage door is opened and the chain drops off your neck, you're afraid to go too far from the cage," she said. "At least it's safe in there." Original Source:Great Falls Tribune March 15, 1999 |

FAS Community Resource Center